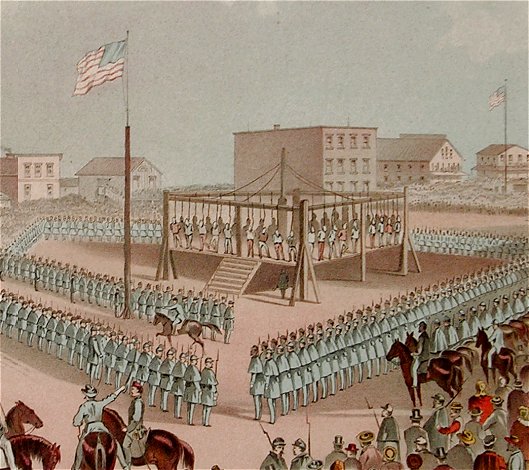

Above, you will find a fascinating– though exceptionally disconcerting– image that captures one of the lowest points in the history of the treatment of Native American Peoples by the government and citizens of the United States.

The print depicts the largest mass execution in the history of the United States when 38 Dakota Sioux were publicly hanged on a single scaffold platform. Although this was a truly horrific act, perpetrated by the United States Federal Government, it could have been MUCH worse– 303 Dakota were sentenced to be hanged by the trial court that sent these 38 to the gallows and, if not for the commutation of the sentences of 264 of the men by President Abraham Lincoln, this scene would have been repeated over and over again (Lincoln allowed the execution order for 39 of the Dakota, but one man given a reprieve).

The image depicts the gallows scaffold in the center, on which the condemned stand, each wearing a hangman’s noose. A large American Flag flies from a towering flag pole next to the scaffold. Surrounding the gallows are double ranks of U. S. Army foot soldiers and an outer ring of mounted cavalry. At the foreground right, there is a crowd of civilian onlookers, and at the left horse drawn, open wagons awaiting to remove the bodies of the condemned men. The lithograph captures the moment before the floor of the gallows was to drop open with the cutting of a single rope. Although the crowd is large, the image presents an almost eerie sense of pause and silence.

This image is taken from a drawing done by a newspaperman who attended the execution in 1862, and it was published in a crude and small size stone lithograph at the time. In more modern years, it appeared in a contemporary issue of Harpers Weekly. This chromolithograph by Hayes is the first (and only 19th century) high quality, color lithograph of the event. Examples of this 1883 Hayes Lithograph hang in various collections and galleries around the country, and are highly prized.

The Dakota War of 1862, also known as the Sioux Uprising (and the Dakota Uprising, the Sioux Outbreak of 1862, the Dakota Conflict, the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862, or Little Crow’s War), was an armed conflict between the United States and several bands of the eastern Dakota people (Sioux). It began on August 17, 1862, along the Minnesota River in southwest Minnesota. It ended with a mass execution of 38 Dakota men on December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota.

Throughout the late 1850′s, treaty violations by the United States and late or unfair annuity payments by Indian agents caused increasing hunger and hardship among the Dakota. Traders with the Dakota previously had demanded that the government give the annuity payments directly to them (introducing the possibility of unfair dealing between the agents and the traders to the exclusion of the Dakota). In mid-1862 the Dakota demanded the annuities directly from their agent, Thomas J. Galbraith. The traders refused to provide any more supplies on credit under those conditions, and negotiations reached an impasse.

On August 17, 1862, four Dakota killed five American settlers while on a hunting expedition. That night, a council of Dakota decided to attack settlements throughout the Minnesota River Valley to try to drive whites out of the area. There has never been an official report on the number of settlers killed, but estimates range from 1200 to 1800. Over the next several months, continued battles between the Dakota against settlers and later, the United States Army, ended with the surrender of most of the Dakota bands. By late December 1862, soldiers had taken captive more than a thousand Dakota, who were interned in jails in Minnesota.

In early December, 303 Sioux prisoners were convicted of murder and rape by military tribunals and sentenced to death. Some trials lasted less than 5 minutes. No one explained the proceedings to the defendants, nor were the Sioux represented by a defense in court. President Abraham Lincoln personally reviewed the trial records to distinguish between those who had engaged in warfare against the U.S. versus those who had committed crimes of rape and murder against civilians.

Henry Whipple, the Episcopal bishop of Minnesota and a reformer of U.S. policies toward Native Americans, urged Lincoln to proceed with leniency. On the other hand, General Pope and Minnesota Senator Morton S. Wilkinson told him that leniency would not be received well by the white population. Governor Ramsey warned Lincoln that, unless all 303 Sioux were executed, “[P]rivate revenge would on all this border take the place of official judgment on these Indians.” In the end, Lincoln commuted the death sentences of 264 prisoners, but he allowed the execution of 39 men.

This clemency resulted in protests from Minnesota, which persisted until the Secretary of the Interior offered white Minnesotans “reasonable compensation for the depredations committed.” Republicans did not fare as well in Minnesota in the 1864 election as they had before. Ramsey (by then a senator) informed Lincoln that more hangings would have resulted in a larger electoral majority. The President reportedly replied, “I could not afford to hang men for votes.”

One of the 39 condemned prisoners was granted a reprieve. The Army executed the 38 remaining prisoners by hanging on December 26, 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota. It remains the largest mass execution in American history. In April 1863, the rest of the Dakota were expelled from Minnesota to Nebraska and South Dakota. The United States Congress abolished their reservations.